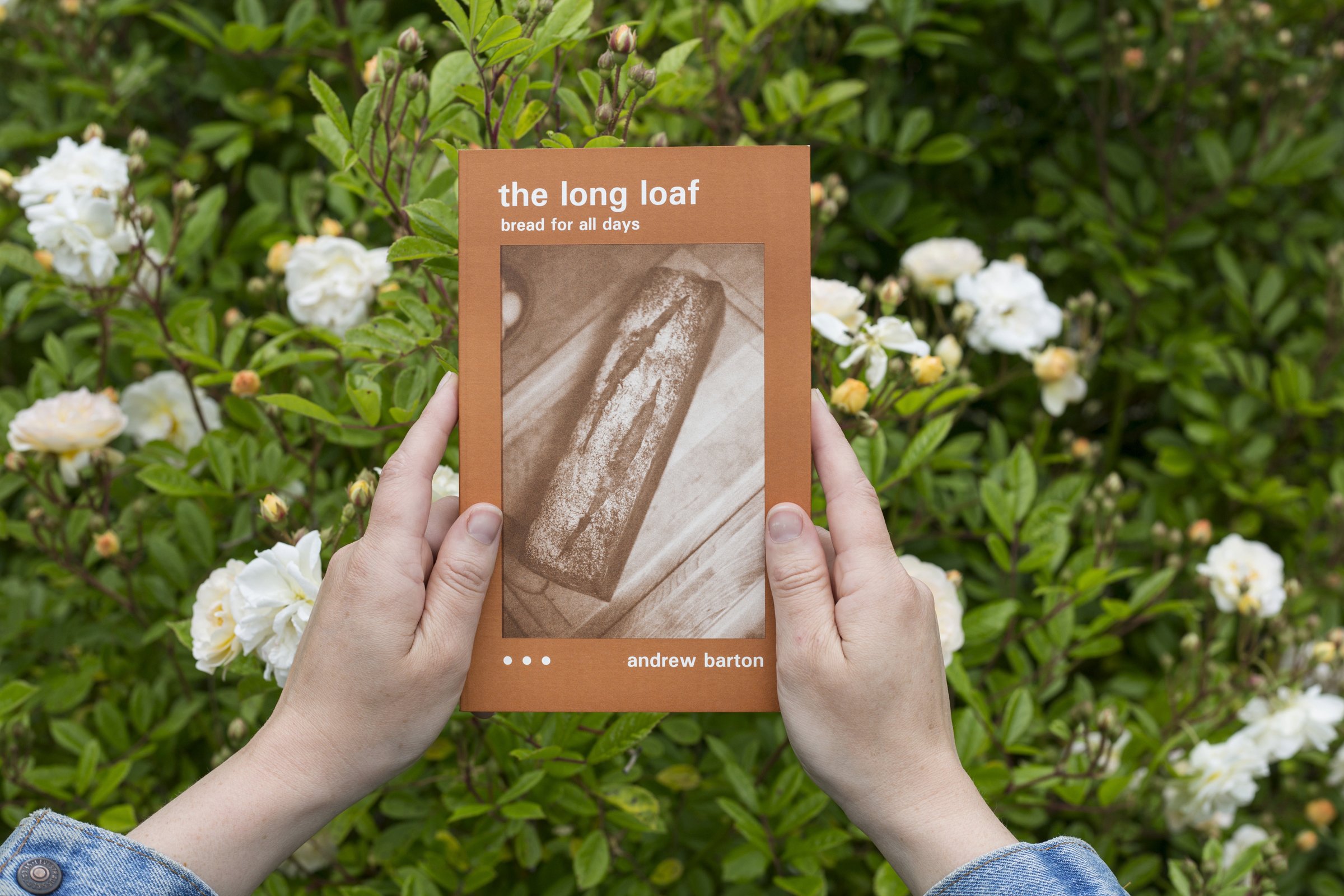

THE LONG LOAF: Bread for All Days – Andrew Barton

THE LONG LOAF: Bread for All Days – Andrew Barton

NOTE:

The first printing sold out in October 2022! See the ‘Nickel Dinner’ page to read praise for the first edition.

The second printing is now available – November 2022.

December 2023 update: We are down to the final box of this edition and it is uncertain how, or if, a third edition will come into existence. This goes to say; if you have been meaning to pick up this book, perhaps now is the time.

Please write to twoplumpress@gmail.com for wholesale inquiries.

ABOUT:

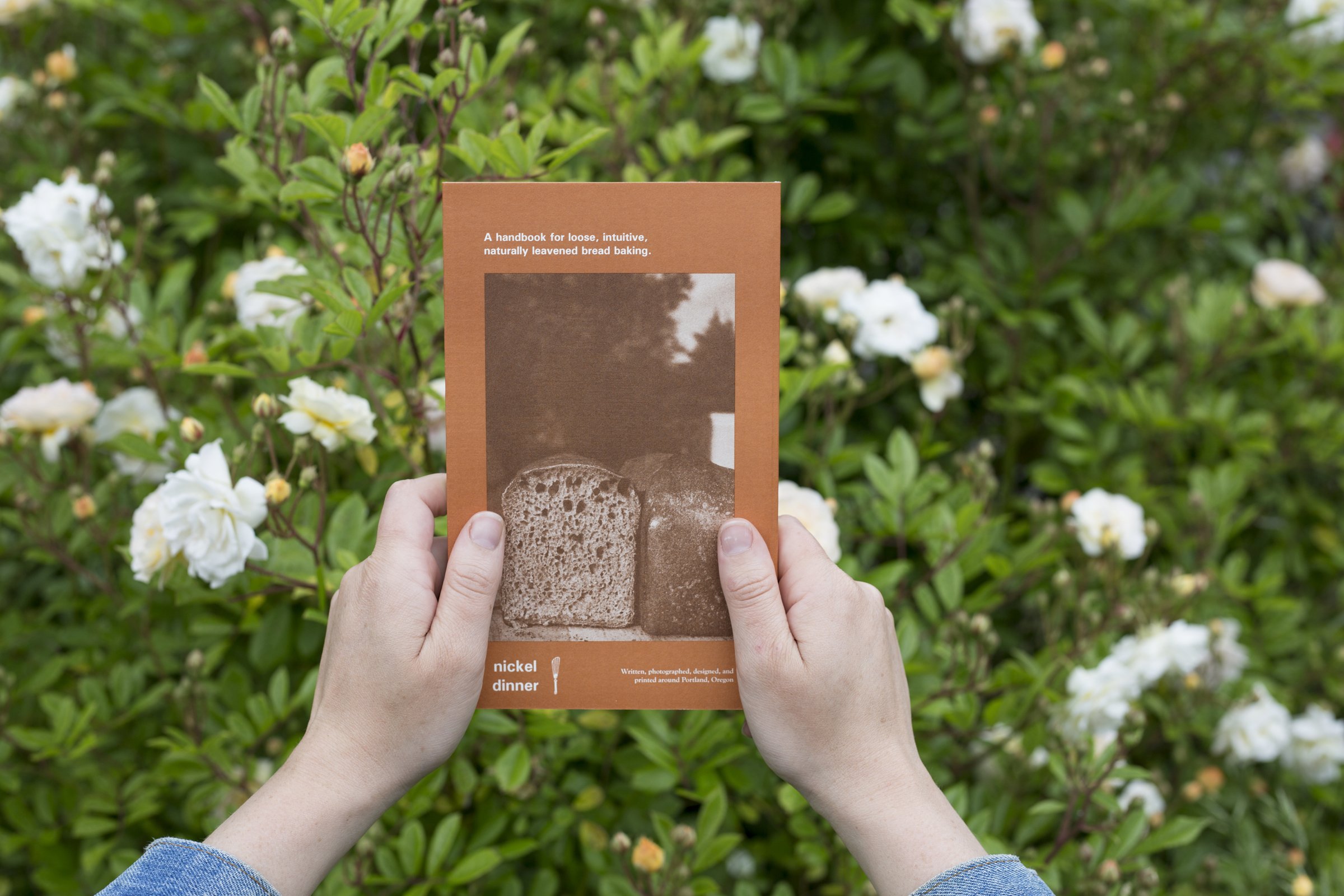

A handbook for loose, intuitive, naturally leavened bread baking peppered with ponderings, ruminations, and romantic notions on the baking and consuming of bread as something one can and should do in our troubled world.

Revive your bread making practice, start or refine one, and enjoy reading about the topic in new ways. ‘The Long Loaf’ presents an approach to simplify and sustain!

Text, photographs, and book design by Andrew Barton.

The first release from NICKEL DINNER, the new culinary imprint of Two Plum Press. Offset printed on high quality paper stock here in Portland, Oregon by Charles Overbeck (Eberhardt Press), who also bound and trimmed every book by hand.

160 pages. A limited printing.

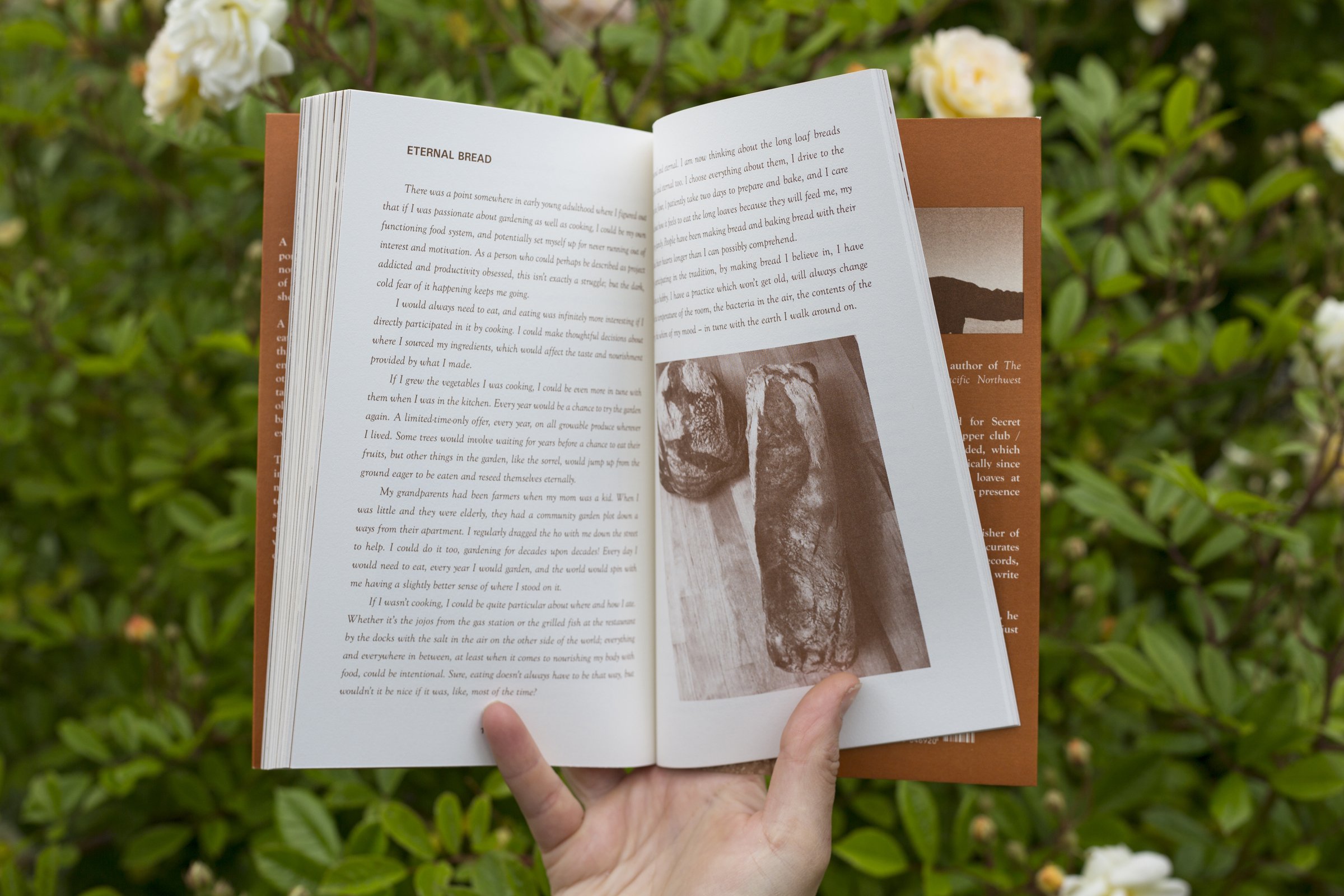

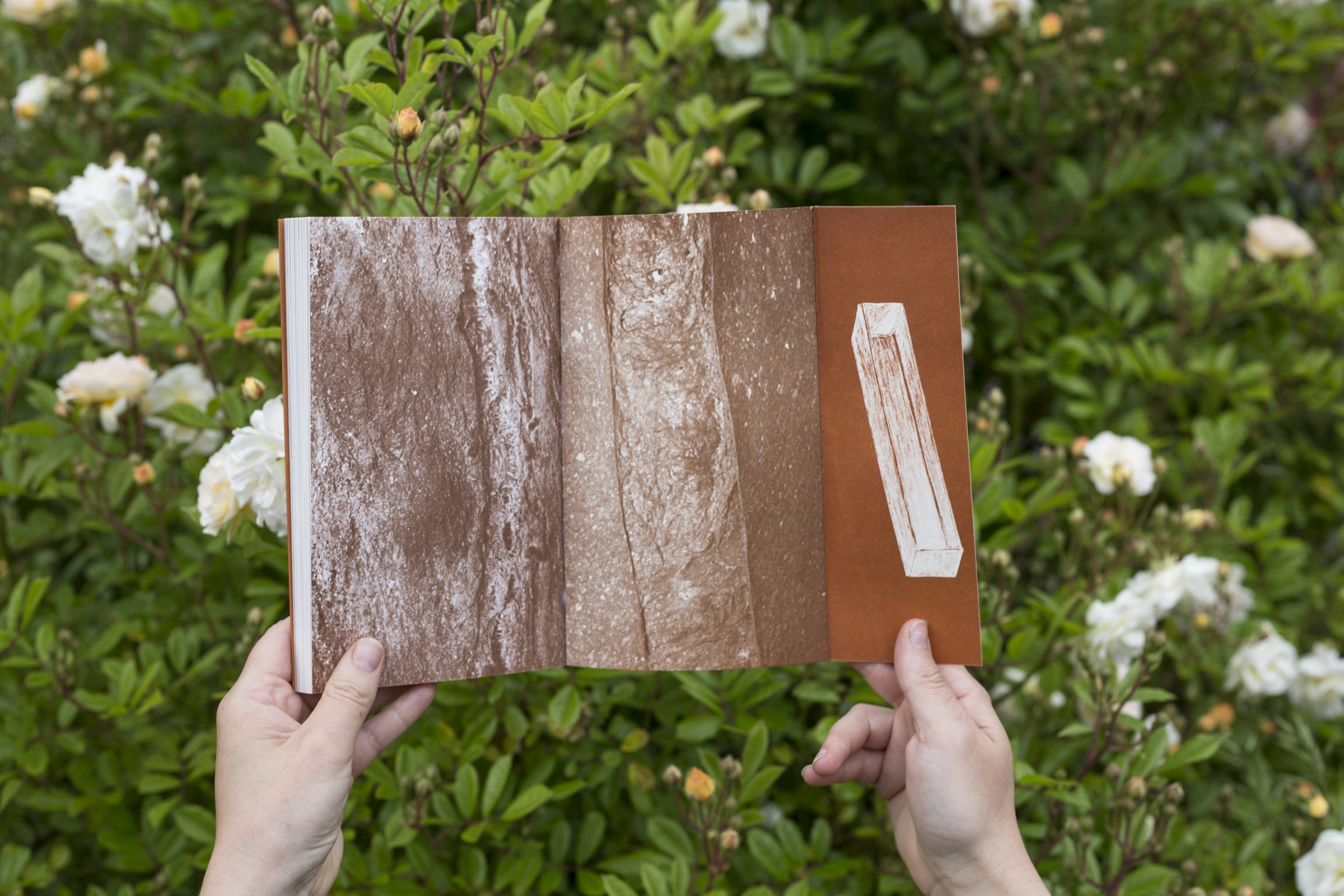

A long loaf is a delight to bake and to eat. Making and baking bread at home this way is versatile – sometimes to be enjoyed slowly throughout the week, other times as a bounteous center of the table. The bread can be a celebration of old and new grains being grown and baked with intention, amplified by the extraordinary flavors to be found. The methods used are easier, more intuitive, and more adaptable than you might think. This book is an invitation to make bread for your own pleasure, to stimulate your senses through the experience, and to produce an ideal version of daily bread for your loved ones.

Excerpts:

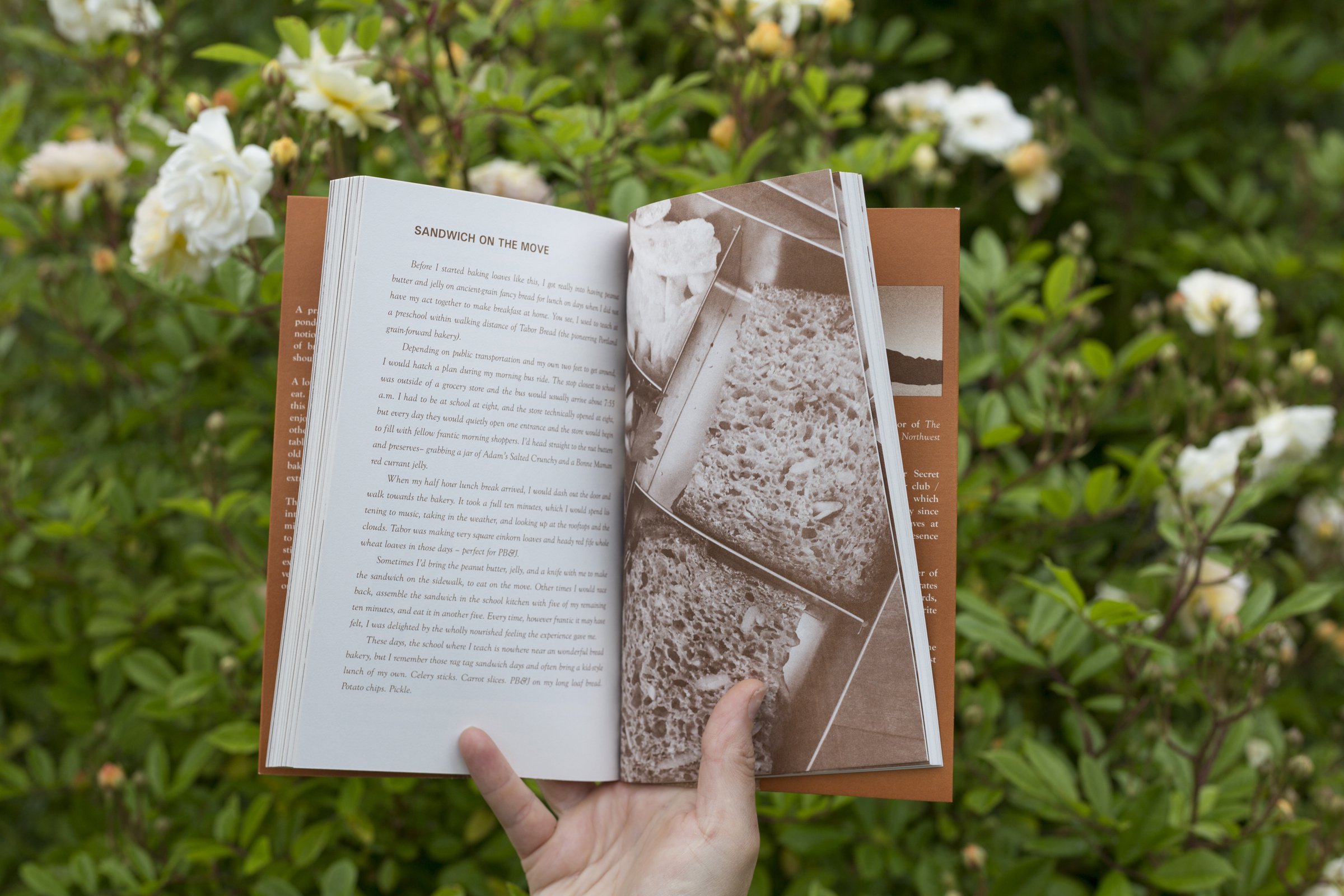

WHAT YOU GET

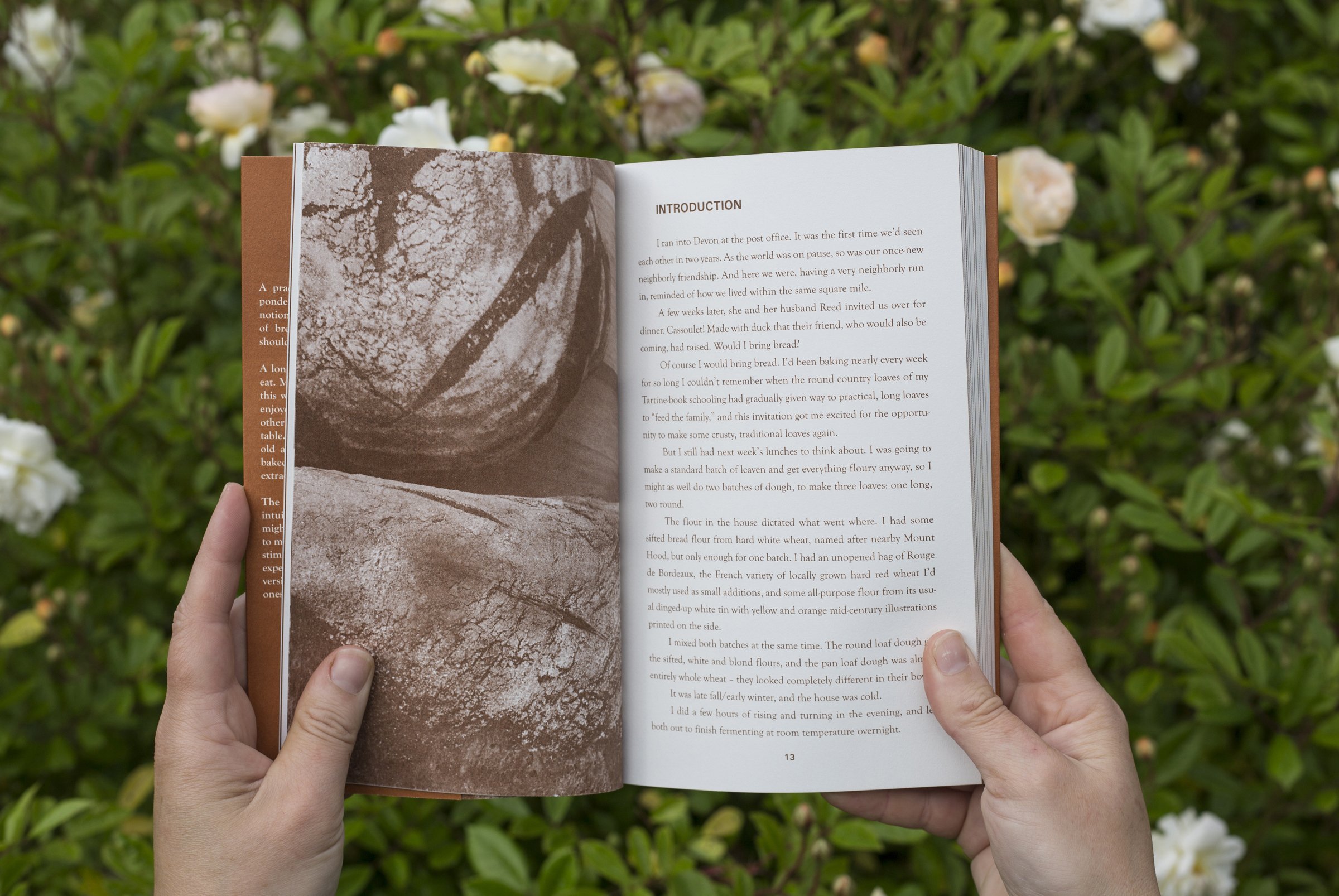

What you get is this outer crust with an almost champagne-bubbles quality crumb to it on three sides. The top crust is more of what you are used to with artisan round loaves, with a shattering caramelized skin and craters of texture from larger air bubbles, scoring, and the magic of every loaf being different.

The inside is springier and spongier than most any bread you’ve had before. When you bite into it, there is a prevailing softness that spreads throughout the nerves in your mouth. Evenly spaced, abundant air bubbles fill the rectangle. This surface was made for butter. When spread with anything – for snacks on the first day, for sandwiches, for toast – the craters fill evenly. The open arms of the bread.

The flavor is at once gentle and comforting, with a tangy note lingering above as you chew. It carries on too. I know from many, many drives to work with a piece of toast on a wooden plate as my passenger seat companion. A bite at a stoplight, the flavor lingering through the entire song between slow downs.

In this bread, I taste all the best loaves I have tasted before somewhere in the background and feel, in the moment, closer to the ever-churning development of grains as they are now, simultaneously ancient and modern.

Eating the bread is also joyous, my tongue freaking out a little as I smile to myself, nourished and fully living.

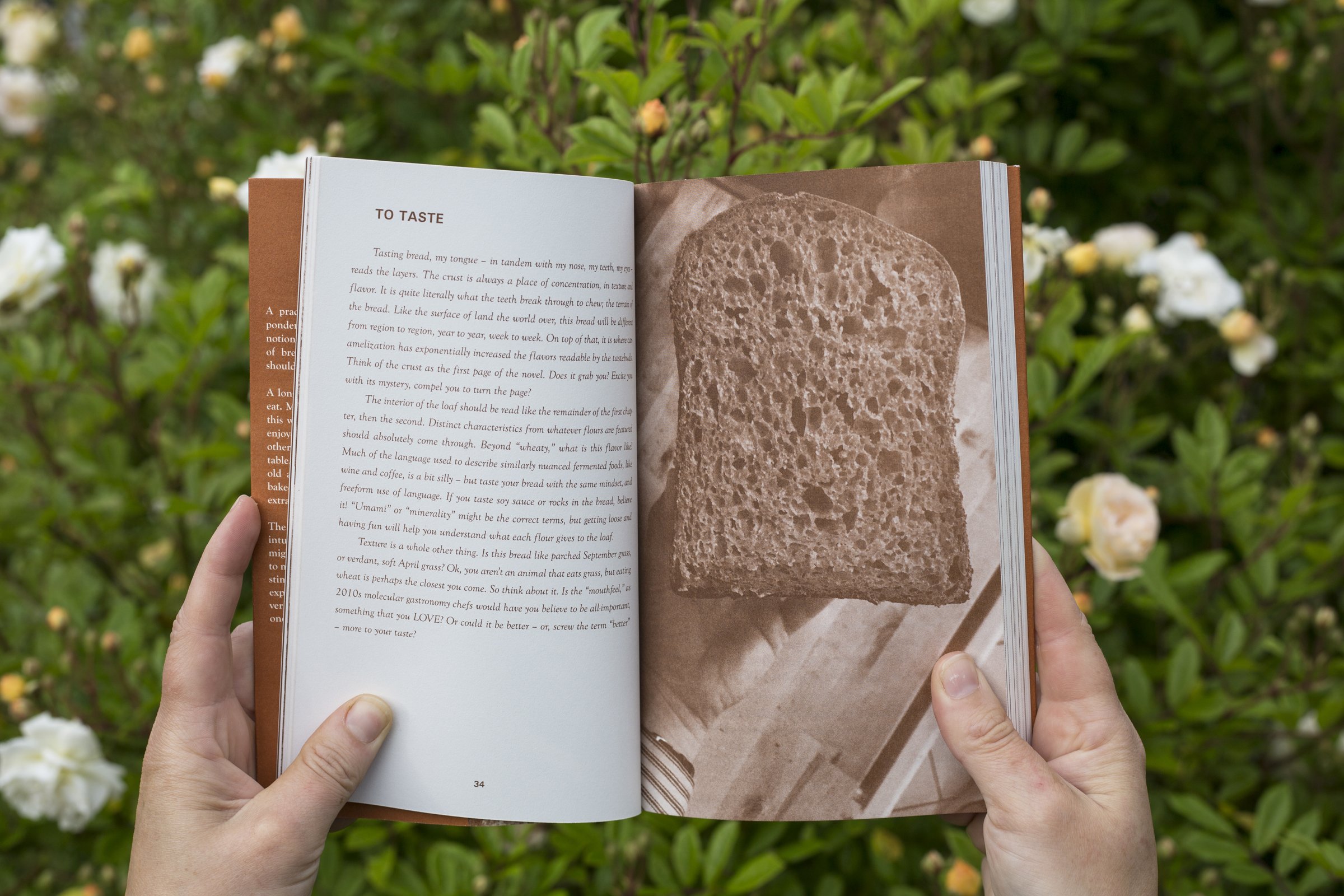

TO TASTE

Tasting bread, my tongue – in tandem with my nose, my teeth, my eyes – reads the layers. The crust is always a place of concentration, in texture and flavor. It is quite literally what the teeth break through to chew; the terrain of the bread. Like the surface of land the world over, this bread will be different from region to region, year to year, week to week. On top of that, it is where caramelization has exponentially increased the flavors readable by the tastebuds. Think of the crust as the first page of the novel. Does it grab you? Excite you with its mystery, compel you to turn the page?

The interior of the loaf should be read like the remainder of the first chapter, then the second. Distinct characteristics from whatever flours are featured should absolutely come through. Beyond “wheaty,” what is this flavor like? Much of the language used to describe similarly nuanced fermented foods, like wine and coffee, is a bit silly – but taste your bread with the same mindset, and freeform use of language. If you taste soy sauce or rocks in the bread, believe it! “Umami” or “minerality” might be the correct terms, but getting loose and having fun will help you understand what each flour gives to the loaf.

Texture is a whole other thing. Is this bread like parched September grass, or verdant, soft April grass? Ok, you aren’t an animal that eats grass, but eating wheat is perhaps the closest you come. So think about it. Is the “mouthfeel,” as 2010s molecular gastronomy chefs would have you believe to be all-important, something that you LOVE? Or could it be better – or, screw the term “better” – more to your taste?

NOT TOAST TOAST

My friend Adam and I were heading to Sauvie Island to cook a meal outside, at our spot near the pioneer apple orchard. It was October, a week or two before Halloween, and the pumpkin patch traffic was absurd. Our plan was to get vegetables from the U-pick farm up the road and improvise, but we’d brought a few things to anchor the meal around.

We sat in the nearly completely stopped traffic for half an hour, then 45 minutes, then an hour. It was already lunch time – late lunch time – and there was no way we’d get materials and cook before getting deliriously hungry, so I opened the bag of provisions.

Two slices of my House Loaf. A jar half-full of aioli I’d made the night before, for dinner at home. Some olive-oil-packed anchovies. Another half jar with just a few spoonfuls of salsa verde. I pulled a metal bowl from the backseat as a lap work-surface, then spread the untoasted bread loosely with the aioli, blotted each with green sauce, and lay the anchovies flat.

We ate the not toast toasts in the golden October sunshine, in the car, going five mph, listening to jazz radio and talking about Ideas in a too-lofty way, brought back down to earth by the experience of eating while hungry.