the fox

THE FOX

by D.H. Lawrence

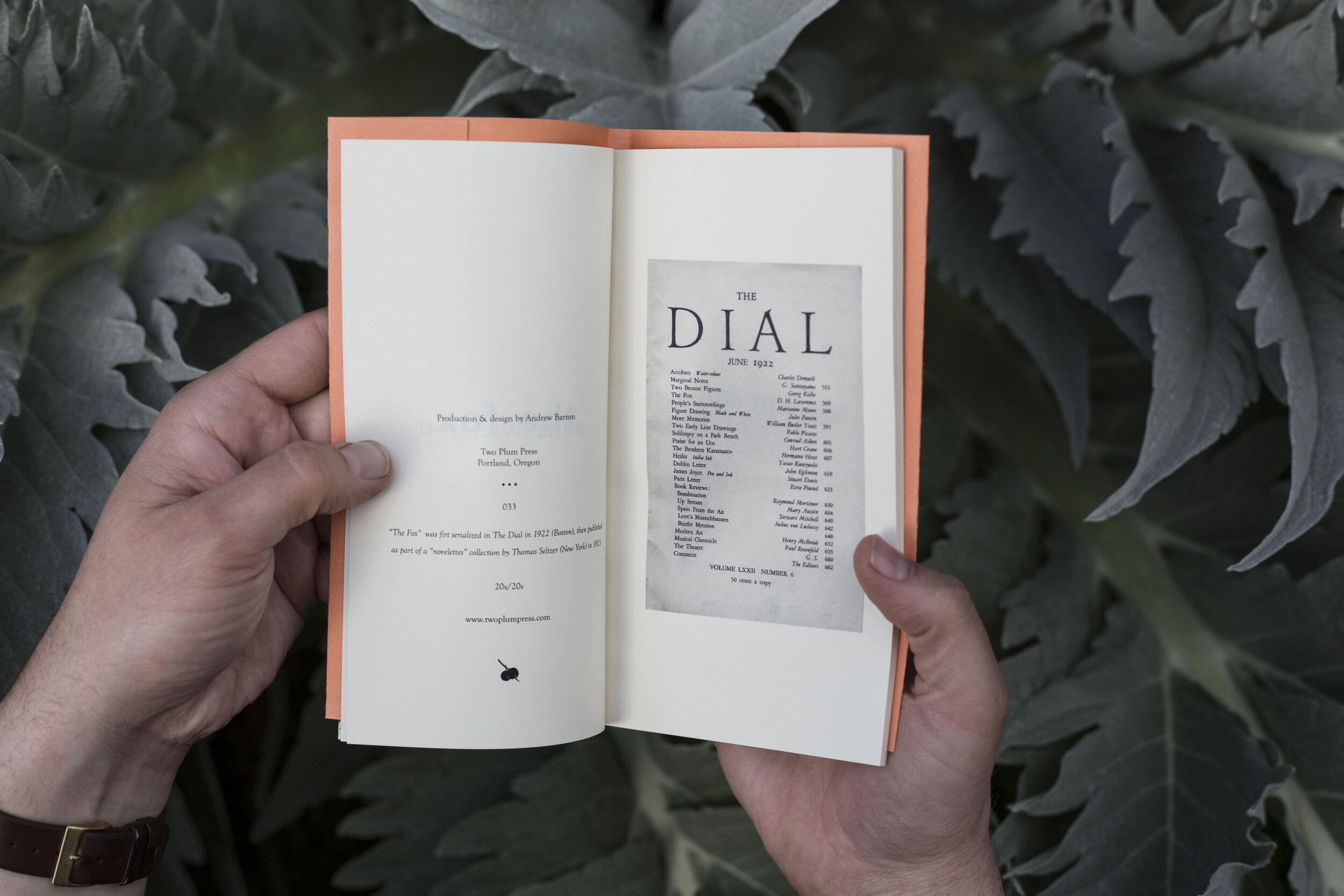

(033)

The Fox (1922) is a novella written during what might be referred to as Lawrence’s middle period, my favorite singular work of his, published hot on the heels of my favorite of his novels, the hardly-ever-discussed The Lost Girl (1920) and his masterful travel book Sea and Sardinia (1921).

The setting is Berkshire during the aftermath of WWI, during the influenza pandemic, making the basic mood rather relevant for our times. In a crumbling farmhouse in the country, two young women farmers work side by side to get by. A fox prowls the grounds, taunting them, evading all capture. The grandson of the previous farmer arrives one day, having no idea that his grandfather would not still be there. Influenza is said to be at the one Inn in town, and he’s got nowhere else to go. The idea if what the townsfolk would think of these two women hosting the young man comes up once, and is quickly dismissed. What ensues is a strange and beguiling romance meets psychological thriller? Maybe that’s taking it too far. When I think of this book I think of candlelight, simple meals of bread and jam, unrealized dreams, windswept hills, sounds in the night.

20s / 20s

20s / 20s is a series of classic slim volume works, published by Two Plum Press in the 2020s. Works featured in the series were originally published in the 1920s and have newly entered the public domain. 20s / 20s is an opportunity for the press to share favorite works by favorite authors of the past, and to uncover lost classics along the way. Placing these works side by side with the press’s contemporary titles is an intentional way to glance back 100 years and to feel the enduring magic of the small book.

excerpt (opening page):

The two girls were usually known by their surnames, Banford and March. They had taken the farm together, intending to work it all by themselves: that is, they were going to rear chickens, make a living by poultry, and add to this by keeping a cow, and raising one or two young beasts. Unfortunately, things did not turn out well.

Banford was a small, thin, delicate thing with spectacles. She, however, was the principal investor, for March had little or no money. Banford’s father, who was a tradesman in Islington, gave his daughter the start, for her health’s sake, and because he loved her, and because it did not look as if she would marry. March was more robust. She had learned carpentry and joinery at the evening classes in Islington. She would be the man about the place. They had, moreover, Banford’s old grandfather living with them at the start. He had been a farmer. But unfortunately the old man died after he had been at Bailey Farm for a year. Then the two girls were left alone.

They were neither of them young: that is, they were near thirty. But they certainly were not old. They set out quite gallantly with their enterprise. They had numbers of chickens, black Leghorns and white Leghorns, Plymouths and Wyandottes; also some ducks; also two heifers in the fields. One heifer, unfortunately, refused absolutely to stay in the Bailey Farm closes. No matter how March made up the fences, the heifer was out, wild in the woods, or trespassing on the neighbouring pasture, and March and Banford were away, flying after her, with more haste than success. So this heifer they sold in despair. Then, just before the other beast was expecting her first calf, the old man died, and the girls, afraid of the coming event, sold her in a panic, and limited their attentions to fowls and ducks.

In spite of a little chagrin, it was a relief to have no more cattle on hand. Life was not made merely to be slaved away. Both girls agreed in this. The fowls were quite enough trouble. March had set up her carpenter’s bench at the end of the open shed.

Here she worked, making coops and doors and other appurtenances. The fowls were housed in the bigger building, which had served as barn and cow-shed in old days. They had a beautiful home, and should have been perfectly content. Indeed, they looked well enough. But the girls were disgusted at their tendency to strange illnesses, at their exacting way of life, and at their refusal, obstinate refusal to lay eggs.